“Do not allow people to encroach onto the state land in Pahang. I am also angered…many people intrude on state land,” he said during a speech in mid-April, according to the New Straits Times.

“It is time for us to stand firm with encroachers who enter the Pahang land without permission. We will act in such a way and it will be solved amicably.”

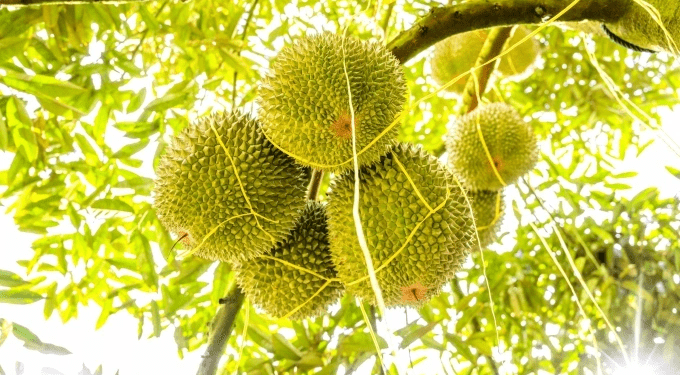

The Pahang government previously chopped down over 1,000 trees, many of which were of the highly valued Musang King variety, as part of a nearly month-long enforcement operation against durian farms on illegally occupied land that started in early April.

The Save Musang King Alliance (Samka), which represents about 1,000 unlicensed durian farmers in the district, and Raub Member of Parliament Chow Yu Hui have strongly opposed the enforcement action.

The operation forms part of a broader dispute over durian orchards that have been cultivated for generations on state-owned land in Pahang without official recognition from either the government or Royal Pahang Durian, which now holds the lease to the disputed land.

Pahang is the main growing region for the prized Musang King variety, which dominates the country’s durian export industry.

Its Raub district, often dubbed Malaysia’s durian capital and nicknamed “Musang King Durian Town,” has an estimated 150,000 durian trees across 2,000 hectares of state land.

Since mid-2024, enforcement efforts have led to the clearing of some 15,000 trees from roughly 202 hectares, according to a video posted by the Pahang Sultanate on Facebook on May 9.

As tensions simmer over the issue, the Sultan of Pahang has voiced his shock and anger over the issue. In early May, he personally drove to one of the former illegal orchards near Raub after learning that 10,521 hectares of land, roughly the size of 14,700 football fields, had been unlawfully occupied in the district, according to national news agency Bernama.

Unlicensed farmers speak out

Some of the affected farmers told The Straits Times earlier this month that their ancestors were encouraged to cultivate state-owned land decades ago by the federal government’s Green Book program, which was launched in 1974 to boost food production and self-sufficiency by promoting farming, including on unused or under-utilized land.

While many of those early farmers hoped that they would eventually own the land, the program did not grant any formal land rights and its primary goal was agricultural output, regardless of ownership.

Chow explained that farmers were given verbal assurances, but no written agreements. Nonetheless, he pointed out that some began working on the land as early as the 1960s with no objections from authorities at the time.

“Some of them started in the 1960s, and the local authorities didn’t block them from going in. After the Green Book programme encouraged farmers to cultivate, more farmers went in,” he noted, adding that farmers believed their efforts were backed by the government.

While some farmers in the dispute have said their trees were decades old, authorities have also found trees aged around eight to nine years on the land—evidence suggesting more recent encroachments, according to Free Malaysia Today. Durian trees generally take four to six years to bear fruit when grown from grafts, and up to a decade if planted from seed.

Over the years, some farmers say they have repeatedly applied for legal land titles, only to be turned down without any explanation.

Wilson Chang, president of Samka, said his family has been farming on a 3.2-hectare plot since 1968 and made numerous attempts to legalize its status.

“We have submitted eight applications (to the state authorities since then), and all of them were rejected,” he said.

Despite decades of cultivation, farmers embroiled in the dispute say they are now unable to benefit from the land they have long worked on.

One of them, a 65-year-old Chinese Malaysian, said they now have no income as they have, for a year, been barred from accessing the land that their families have farmed for generations.

“I have to take on odd jobs at other people’s farms, like spraying pesticides,” the person said. “I can’t sleep at night. I have no money and no future.”

Royal Pahang Durian, chaired by the Pahang Sultan’s daughter, Tengku Puteri Iman Afzan al-Sultan Abdullah, has offered to lease the land back to the farmers on the condition that they sell their durians exclusively to the group at a fixed price far below the market rates, according to the South China Morning Post.

Chow said the group set the price at RM35 (US$8.18) per kilogram for grade A (highest quality) Musang King durians and RM18-22 for grade B fruits while the market rates for the prized variety are three to four times higher.

The Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, which has been investigating the matter, said last month that it was tracing witnesses dating back to 2004 and gathering related documents and testimonies.

The agency’s chief commissioner, Tan Sri Azam Baki, said it was also considering investigating the issue under laws addressing the dishonest use of property.

“So we are now looking at both criminal elements and governance issues. We are also investigating corruption, particularly involving enforcement officers who are suspected of receiving bribes at the time,” he noted.

Malaysia exported over 27,000 tonnes of durian in 2023, generating US$44.49 million in export revenue, figures from global trade data provider TradeImeX shows. Its export volume surged last year after it secured an agreement with Beijing to allow the export of fresh durians to China, which had previously been limited to frozen ones.